“Director James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown is an engaging, if superficial, Bob Dylan biopic.”

Pros

- Four impressive lead performances

- A strong, immersive sense of time and place

- Several well-staged musical performance scenes

Cons

- A surface-level screenplay

- An anticlimactic conclusion

- A thinly drawn central romance

Few artists have ever maintained the same levels of fame and impenetrability as Bob Dylan. The genre-redefining American icon is known almost as much for his enigmatic, purposefully aloof persona as he is for his dense, enduring lyricism. It would seem then a foolhardy endeavor to try to find your way into his closely guarded psyche. The closest one could hope to get would be in a more abstract work like Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, which tries to create a complete portrait of Dylan in all of his enigmatic elusiveness by having six different actors all play him at various points.

If it tried to dive any further into its subject’s mind than I’m Not There, a straightforward, fact-based biopic like director James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown would seem doomed from the start. It comes as both an unexpected and welcome surprise then that A Complete Unknown isn’t all that concerned with who Bob Dylan is or why he wrote the songs that electrified an entire generation of counterculturalist listeners in the 1960s. The film’s interest in such matters is, in fact, succinctly summed up in one memorable scene when a young Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) responds to one of her fellow folk singer’s stories about learning how to play the guitar from other members of a traveling circus by incredulously asking, “You were in a carnival?”

Dylan (Dune: Part Two star Timothée Chalamet) replies to her question with an unanswering, blank stare. It’s a fitting response for both an artist so deliberately withholding and a film as uninterested in investigating how Bob Dylan sees himself as a complete unknown. The movie is wisely and, perhaps, inevitably more interested in how everyone else saw him when he emerged in the early ’60s, how they each hoped to use and control him, as well as how terrifying, exciting, and humbling it is to come face to face with someone whose talent is undeniable.

Based on Elijah Wald’s book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, A Complete Unknown follows Chalamet’s Bob Dylan as he arrives in New York City in 1961, quickly climbs his way up the hierarchy of the American folk scene, and becomes so popular that he begins to bristle against the immovability created by his own fame. The film spans just the first four years of Dylan’s career. Its screenplay, co-written by Mangold and frequent Martin Scorsese collaborator Jay Cocks, divides this period into two halves, both of which climax with performances at the Newport Folk Festival. The first, an acoustic rendition of The Times They Are a-Changin’, works as a rousing crowning of Dylan as the new king of folk. The second, Dylan’s infamously rowdy live electric debut in 1965, is well-staged by Mangold, but struggles to match the gravitas of its predecessor, partly because A Complete Unknown slightly oversells the trend-bucking nature of its subject’s sonic swerve.

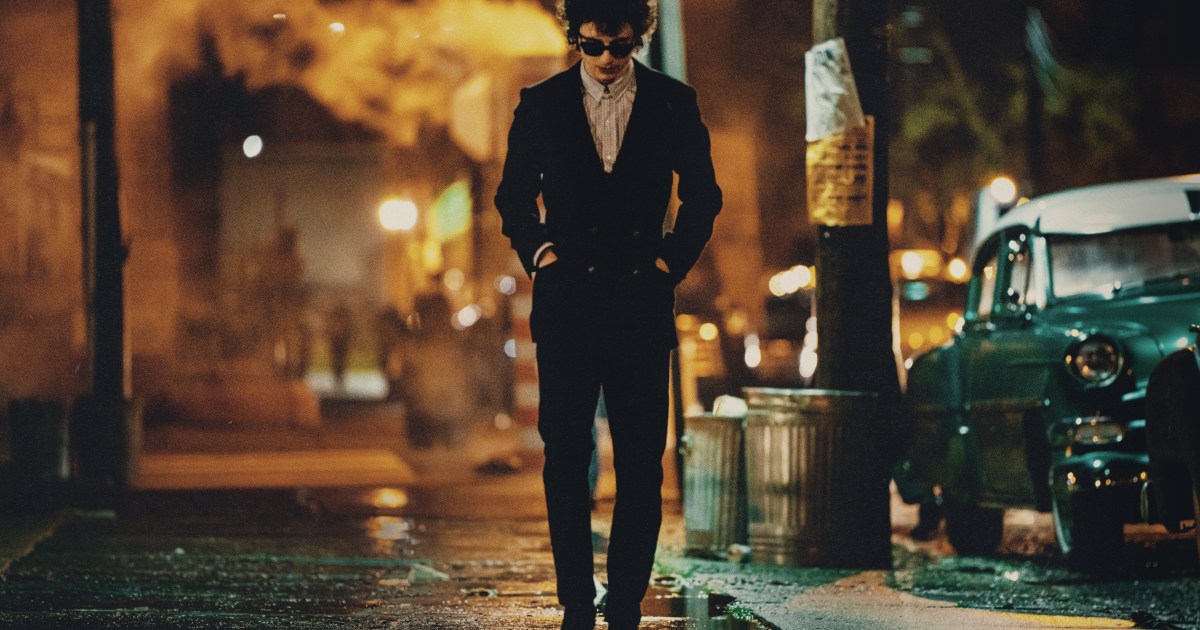

These scenes, as well as all the performances in A Complete Unknown, only work in any capacity because of Chalamet’s star turn as Dylan. The young actor does his best to replicate his inspiration’s distinct, nasally yet gravelly voice, and he largely succeeds. At times, his grasp on Dylan’s voice and mannerisms borders on questionable imitation, but Chalamet, for the most part, resists the urge to do too much. Over the past several years, the actor has grown increasingly comfortable in front of the camera, and A Complete Unknown, while being neither his best film, nor his best acting showcase, marks the culmination of his up-and-coming movie star journey. Here, he seems well aware of the power his mere presence holds, and he knows that he has to do very little other than stand and look a certain way to keep your eyes glued to him at all times.

Mangold surrounds Chalamet with supporting performances that miraculously match the simple power of his lead actor. Edward Norton, in particular, makes a mark with his gentle, yearning turn as longtime activist and folk musician Pete Seeger, who meets Chalamet’s Dylan when the latter decides in A Complete Unknown‘s spell-binding, surprisingly tender opening scene to visit his hospitalized idol, Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy, giving a transformative, wordless physical performance). Sitting on the other side of Guthrie’s bed, Pete takes an immediate liking to Bob, inviting him to stay with his family and helping him ingratiate himself within the bustling Greenwich Village folk community. Elsewhere, Barbaro gives a strong, scene-stealing turn as Joan Baez, an already successful and established folk musician whose attraction to Chalamet’s Bob mystifies her — but not enough to stop her from taking advantage of his songwriting talent or letting him simply walk over her.

Norton and Barbaro’s lived-in performances aid A Complete Unknown in its efforts to recreate the New York City of the early ’60s. Whether it be wide shots of Chalamet walking past the Chelsea Hotel or even a small detour into the recreated Gaslight Café, the film does its best to immerse viewers in a specific American subculture during a period when it was at its buzziest. Credit must be given to production designer François Audouy and cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, the latter of whom covers A Complete Unknown in a colorful warmth that just makes its setting all the more alluring and inviting. While the film does stretch itself to find a role in its story for Johnny Cash (a charming, convincing Boyd Holbrook), it doesn’t pack in too many distracting references and historical cameos, either. It remains focused on charting Dylan’s rise and the tensions that gradually form between him and those around him along the way, though, some of its interpersonal conflicts work better than others.

Baez’s on-again, off-again affair with Bob suffers from the film’s bifurcated structure. Although Elle Fanning’s performance as Sylvie Russo, the girlfriend who helps steer Chalamet’s Dylan toward more politically minded subject matter, is endearing and affecting, too, their relationship is never given A Complete Unknown‘s full attention. Her heartbreak over Bob’s blasé attitude toward their romance isn’t, therefore, as impactful as it might have been were the film more invested in trying to explore its protagonist’s interior life. The closest it comes to doing so is in a late-night visit Bob pays to Sylvie in A Complete Unknown‘s second half after a violent encounter with a possessive fan. Seeking comfort, Bob ignores the other man sleeping in Sylvie’s apartment and presses a cold washcloth to the bruise under his eye. “Everyone asks where the songs come from, but when you watch their faces, they’re not asking where the songs come from,” he bitterly tells Sylvie. “They’re asking why they didn’t come to them.” Where this realization comes from is unclear within A Complete Unknown‘s framework, but the envy alluded to in this scene turns out to be at the heart of the film and its take on Bob Dylan’s story.

It most successfully explores this feeling through Norton’s Pete, a kind folk purist who quickly sees in Bob the kind of attention-grabbing potential he’s long believed the folk scene and its political ideals has needed. He does his best to elevate Bob, and he delights in seeing his and Guthrie’s initial efforts to revive the folk music movement begin to bear fruit. When Bob, however, starts to move away from Pete’s ideas about the purity of acoustic songwriting and experiment with electric, rock-driven instrumentation, contentious questions arise about Bob’s say over his own music and his responsibility to the community that shined a light on him in the first place. Norton, for his part, masterfully conveys this conflict with the hopeful, puppy-dog looks he throws Chalamet’s way whenever Pete is watching Bob play or even performing with him.

A Complete Unknown indulges in many of these moments. Chalamet brings a perpetually glazed-over quality to his eyes that makes it seem as though he is always looking both everywhere and nowhere in particular. This quality only makes Chalamet’s performance stand apart further from his co-stars’, with Barbaro, Fanning, and Norton all asked in multiple scenes to stand and watch with a tilted head and quizzical eyes as they slowly get swept up in the magic of Dylan’s songwriting. These scenes inevitably feel contrived, and they are common within music biopics like A Complete Unknown. The film makes better use of them than others have throughout the years, though, if only because they make more sense in a drama that is ultimately about the world’s reaction to Bob Dylan and other trailblazers like him.

For better and for worse, A Complete Unknown has little to offer when it comes to introspective thoughts on Bob Dylan’s life and it makes no attempt to ever question his behavior or hold him accountable for any of his many mistakes and unwarranted slights. In its strict, uniquely Mangold-esque formalism, A Complete Unknown doesn’t ever come close to replicating Dylan’s boundary-pushing, inventive spirit, either. But, as a portrait of a culture-changing enigma, it provides an effective and often exciting trip back to a time when America was in desperate need of a new, undaunted voice. It is, more impressively, a surprisingly uncompromising, unsentimental exploration of the ways we try to control the artists we lift up and the fear and the anger we feel when their chosen methods of expression change and evolve in ways that make even their most fervent supporters uncomfortable.

Trying to control Bob Dylan is as misguided an endeavor as trying to understand him. Maybe those two things are the same. If so, A Complete Unknown has no interest in doing either. We don’t, after all, get to choose who is talented and who is not. Why, then, should we get to have any say over what those chosen few do with their gifts?

A Complete Unknown hits theaters Wednesday, December 25.

Read the full article here