This is The Stepback, a weekly newsletter breaking down one essential story from the tech world. For more on all things at the intersection of environment and technology, follow Justine Calma. The Stepback arrives in our subscribers’ inboxes at 8AM ET. Opt in for The Stepback here.

Some stories that I’ve worked on as an environmental journalist still haunt me. One of the first to get under my skin happened to be about forever chemicals.

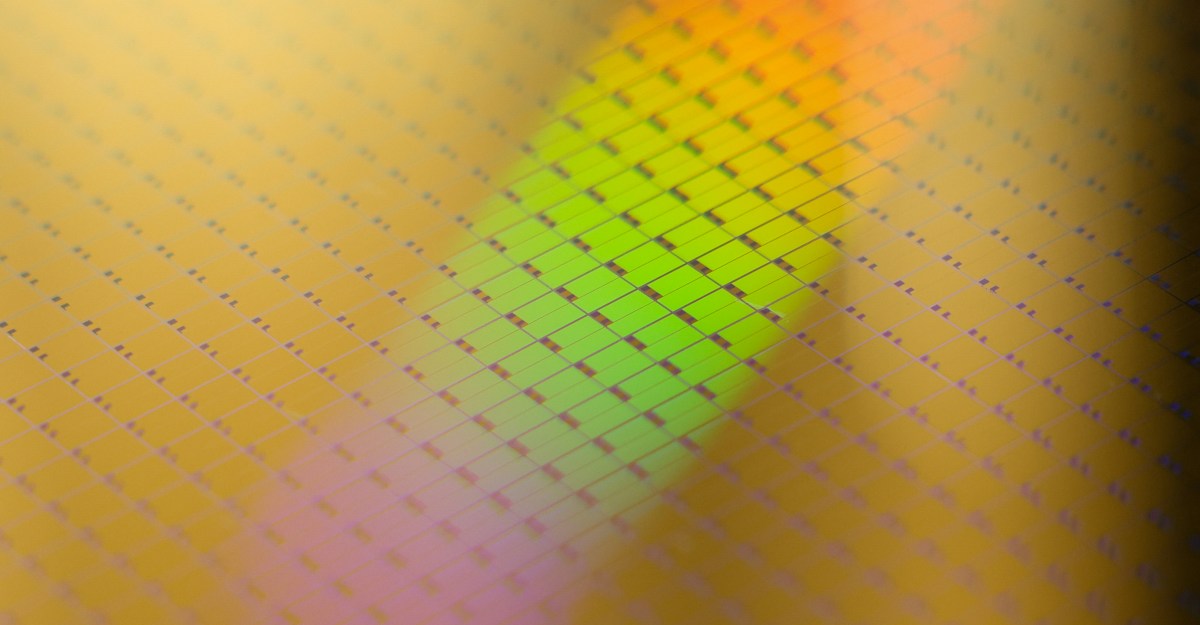

Since the 1940s, forever chemicals have been commonly used by manufacturers as a way to make things resistant to water, stains, and heat. Think food packaging, nonstick pans, water-repellant outdoor gear, and even period-proof underwear. They’re also used to make much of the tech that we’ve come to rely on; one subclass of the chemical is used in lithium-ion battery electrolytes and binders. Now, there’s a growing concern that the chemicals are ubiquitous in computer chip manufacturing, an industry that’s starting to see a resurgence in the US.

Technically known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), they’re called forever chemicals because of particularly strong molecular bonds that keep them from breaking down even in harsh conditions. It’s a trait that also means they can linger in the environment for hundreds or even thousands of years and potentially in the human body for several years. Most people in the US already have PFAS in their blood, according to national health surveys by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that have included PFAS testing since 1999. People eat food and drink water contaminated with the chemicals, or they might be exposed if they live near or work at a factory where there are PFAS.

Researchers are still trying to fully understand the impact that these chemicals can have on the human body. Some of the most widely used forever chemicals have already been linked to health effects such as kidney and testicular cancer, hypertension and preeclampsia in pregnancy, higher cholesterol, and more.

A landslide of lawsuits have forced some companies to do something about their pollution. Companies including 3M (maker of Scotchgard) and Dupont (manufactured Teflon) have subsequently made commitments to phase down or phase out the chemicals. Levels of two of the most prevalent forms of PFAS in Americans’ blood have dropped by 70 and 85 percent as production and use fell over the past couple decades, according to the CDC. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized limits on five of the most common types of forever chemicals in drinking water last year.

Problem solved, right? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. There are actually thousands of different kinds of forever chemicals. And new health concerns have cropped up with chemicals meant to replace the most notorious types of PFAS.

Oh, and deregulation just might be the EPA’s favorite word now under the Trump administration. In May, it proposed rolling back drinking water standards for PFAS. The agency says it plans to extend compliance deadlines for two types of PFAS and rescind existing regulations for the remaining three types.

This is all happening as President Donald Trump follows in former President Joe Biden’s footsteps when it comes to trying to onshore computer chip manufacturing, following the global semiconductor shortage that roiled all kinds of industries from gaming to automobiles. AI, reliant on even more advanced chips, raised the stakes.

Companies that make forever chemicals smell an opportunity. The Dupont-spinoff Chemours, for example, says on its website that its role is “indispensable” in the push to build up a domestic supply chain of semiconductors. The company makes Teflon, which is used in chip manufacturing because of its resistance to heat and corrosion. Chemours is also developing fluids that could be used to cool servers in data centers in a process called two-phase immersion, which typically involves PFAS.

Chemours has already made plans to expand its facilities in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and Parkersburg, West Virginia, to support its ambitions. That has unsurprisingly raised red flags for health and environmental advocates, considering Chemours’ checkered past with PFAS. The Fayetteville facility has been found responsible for contaminating water supply wells and was placed under a consent order in 2019 to limit pollution. In March, North Carolina regulators told Chemours to expand well testing near the Fayetteville facility to an additional 150,000 homes at risk of potential PFAS contamination. And in August, a federal judge ordered Chemours to stop releasing unlawful amounts of forever chemicals into the Ohio River in West Virginia.

It’s not just Chemours that’s under a microscope. Concerns have been raised about new semiconductor fabs in the US, including about the chemicals they use and the risks that they could pose to workers and nearby residents. The Semiconductor Industry Association has actually put together a PFAS Consortium — which Chemours and Dupont joined — because PFAS regulation “appears likely to disrupt the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain and requires a supply chain-wide approach to address,” according to a July 2024 FAQ document.

Now, however, the industry is in a decidedly more chemical-friendly regulatory environment under the Trump administration. Trump’s AI Action Plan aims to speed data center development in part by fast-tracking permitting and slashing environmental reviews for semiconductors facilities and related “materials.” In July, the president granted “certain chemical manufacturers that produce chemicals related to semiconductors” two-year exemptions from Biden-era pollution regulations. And a former chemical industry lawyer, who now has a senior position at the EPA, has worked to undo another Biden-era rule that makes companies responsible for cleaning up the PFAS pollution they create, The New York Times reported.

EPA press secretary Carolyn Holran said in an email to The Verge that the EPA is still “holding polluters accountable” and that “no decisions have been made” regarding the proposed rule change reported on by The New York Times. Chemours is investing in “state-of-the-art emissions control technologies” at its manufacturing sites to reduce chemical releases, spokesperson Jess Loizeaux said in an email to The Verge.

The EPA still has to finalize rule changes and is probably going to face legal battles as it tries to slash water and air protections. It’s already taken forever to start to get a grip on the PFAS problem, and it looks like the chemicals are poised to stick around even longer as the Trump administration prioritizes deregulation and demand for computer chips not letting up.

- Forever chemicals are difficult to clean up because of how hard they are to destroy. They can even stay in the air after being incinerated. Their molecular strength comes from carbon-fluorine bonds that might take temperatures above 700 degrees Celsius (1,292 degrees Fahrenheit) to break apart.

- Forever chemicals in firefighting foams have contaminated military bases across the US, putting servicemembers at risk even when they’re stationed at home.

- Chemours, Dupont, and another company called Corteva reached an $875 million settlement with the state of New Jersey in August over pollution including PFAS.

0 Comments

Read the full article here